Mapping Ain't Modeling

Diagnosing and Evolving Complex Systems

As modern software engineers, many of us live on the edge of a frontier world—testing new tools, exploring non-traditional delivery methods, and trying to improve how software gets built and shipped. But while we push into new terrain, we’re often still tethered to organizations rooted in a traditional mindset of software delivery. It can feel like being a cartographer in a world that actually needs a systems ecologist.

That’s where the difference between mapping and modeling becomes more than academic. I have found that the two terms are often used interchangeably. But treating them as synonyms is a mistake—one that can obscure opportunities for real insight and meaningful improvement.

Diagnostics Over Descriptions

At its core, mapping is a visualization exercise. It shows us where things are. In software terms, process maps can help teams understand the flow of tickets, deployments, or incident handling. It captures an existing system by laying out its structure and relationships—how components connect, how workflows proceed, and what steps occur in sequence. They’re useful for onboarding and documentation.

But maps are static. They’re a snapshot in time. They don’t show what happens when a storm hits the supply chain, when a server crashes mid-deploy, or when your most senior engineer takes leave. They don’t help you anticipate change—they just record the present.

Maps stop short of deeper insight. They don't typically ask why a process behaves a certain way, or how it might evolve. They show the what, but not the why and certainly not what if.

Discovery and Simulation

Modeling, in contrast, is not just representational—it’s analytical. It requires a frontier mindset. It treats your system as a living, evolving organism. A model doesn’t just show the steps in a system; it interrogates them. It reveals dependencies, tests assumptions, and surfaces the logic behind process flows. It’s a dynamic tool that enables teams to simulate change, assess the impact of different decisions, and uncover inefficiencies.

Where mapping is documentation-first, modeling is discovery-driven. It’s not limited to what exists—it explores what could be.

Actionable Insight

Effective process modeling goes beyond structure and sequence. It captures behaviors, feedback loops, potential bottlenecks, and even failure modes. A good model evolves with the system it represents, continuously incorporating new insights as the business or technology changes.

This makes modeling invaluable not just for understanding complexity, but for managing it. It supports better decision-making because it forces deeper consideration of system behavior and potential trade-offs.

Using a hypothetical example, let’s take the case of a SaaS company that wants to improve how it handles bug reports.

Process Mapping

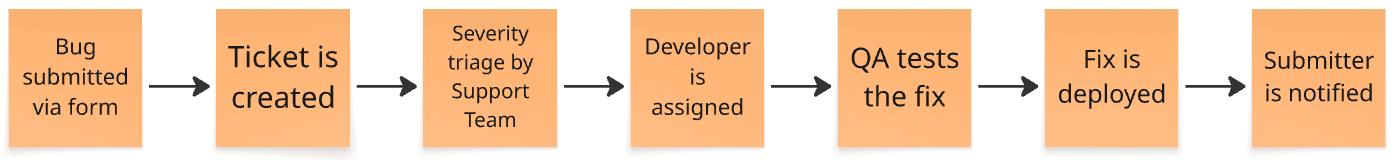

The company maps out the current flow:

This map helps the team visualize handoffs and clarify responsibilities. It's useful. But it is a shallow representation missing important insight.

Process Modeling

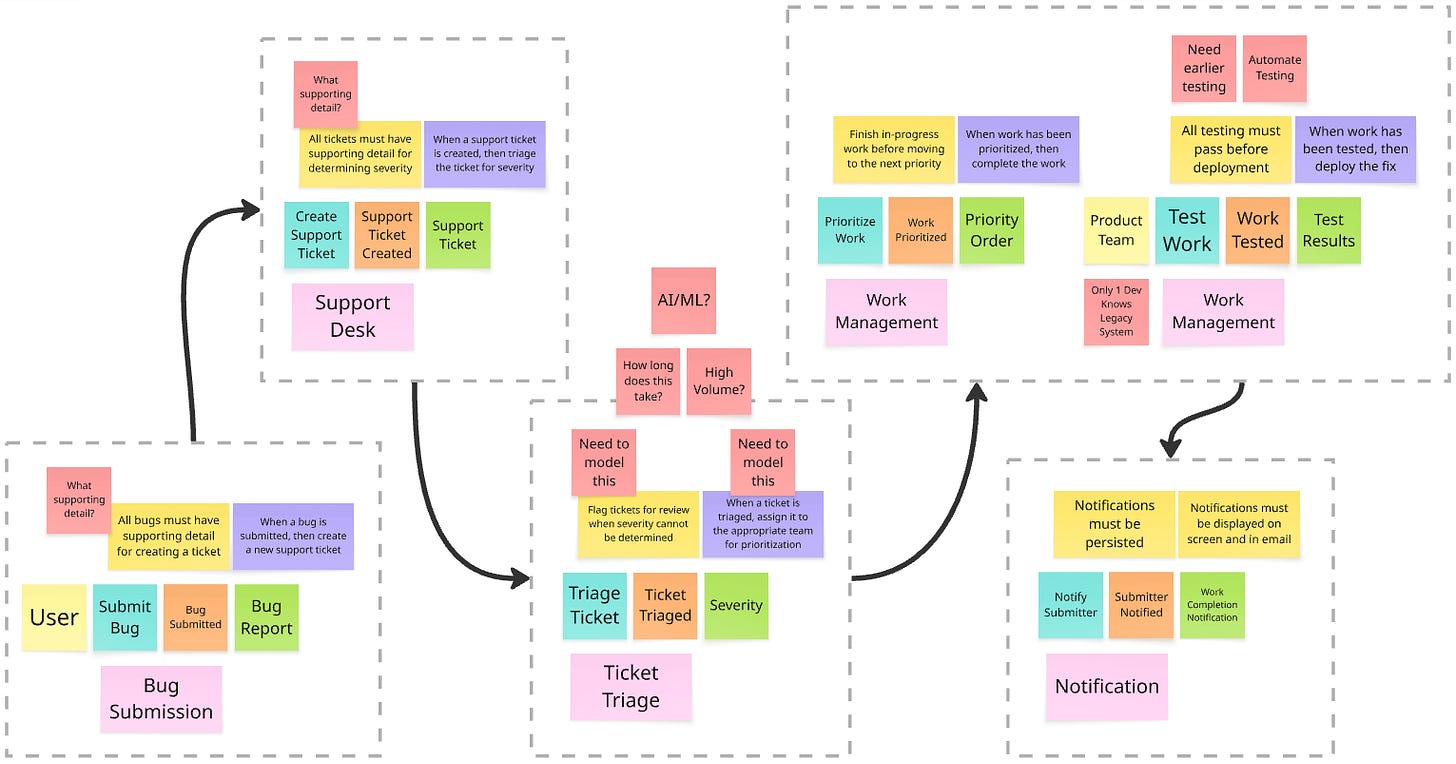

Building a model can lead to useful questions:

How long does triage take on average per bug type?

What happens if report volume triples?

How does dev assignment lag when only one engineer knows the legacy system?

Could an ML-based triage tool shift the bottleneck downstream?

What’s the effect of delaying QA by one sprint?

And far more context:

Now they’re not just documenting—they’re diagnosing. They’re running simulations, testing alternatives, and designing for resilience. This can more directly relate to the desired system state.

Collaborative Modeling

The benefits of modeling expand significantly when it becomes collaborative. Traditional models often live in the minds of analysts and system architects or sit idle in static diagrams buried in wikis and Confluence pages. Collaborative modeling changes the game. It turns the model into a living artifact, co-created by engineers, product managers, designers, operations, and even customers. This approach doesn’t just produce better models—it builds shared understanding, aligns priorities across disciplines, and accelerates decision-making. By making modeling a participatory effort, the entire system benefits from diverse insights and shared ownership. This often leads to systems that are not only better understood, but better designed.

In practice, this might look like a real-time modeling session using tools like Miro following modeling types common to EventStorming. The key is this: everyone brings their lived experience of the system into the model. This surfaces assumptions, exposes blind spots, and catalyzes alignment. Collaborative modeling turns systems thinking from a solo activity into a team sport. And when teams model together, they not only understand the system better—they start to shape it with a shared sense of purpose and accountability.

A Complement, Not a Replacement

To be clear, this isn’t about discarding maps. They’re useful, especially for onboarding, compliance, and communication. But for teams tasked with transformation, optimization, or innovation, maps alone are not enough.

If you’re trying to improve a system—or even just understand it enough to change it—modeling is the tool you need. It turns documentation into diagnosis, and static flow diagrams into dynamic understanding.

When you’re trying to evolve software delivery inside traditional organizations, you're navigating uncharted territory. Process models become your compass. They give you the tools not just to describe the landscape, but to reshape it. They also help you advocate for change with evidence, not intuition.

Maps can guide us through known terrain. But if you're forging new paths in how software gets delivered, models are your survival gear.